This article is available to download (for free) in full, as a standalone report – from here. The report features additional information. It forms part of Enterprise IoT Insights’ ongoing Making Industry Smarter report series, which has also covered Energy & Power, Agriculture & Farming, Supply Chain & Logistics, Cities & Towns, and Production & Manufacturing.

DEEP UNDERGROUND

Mining is unlike any other ‘heavy’ industry. Production follows the source; rock is crushed, mineral is excavated, and production moves on. It is also a harsher environment in which to work, especially underground, and a tougher place to bring machinery and connectivity.

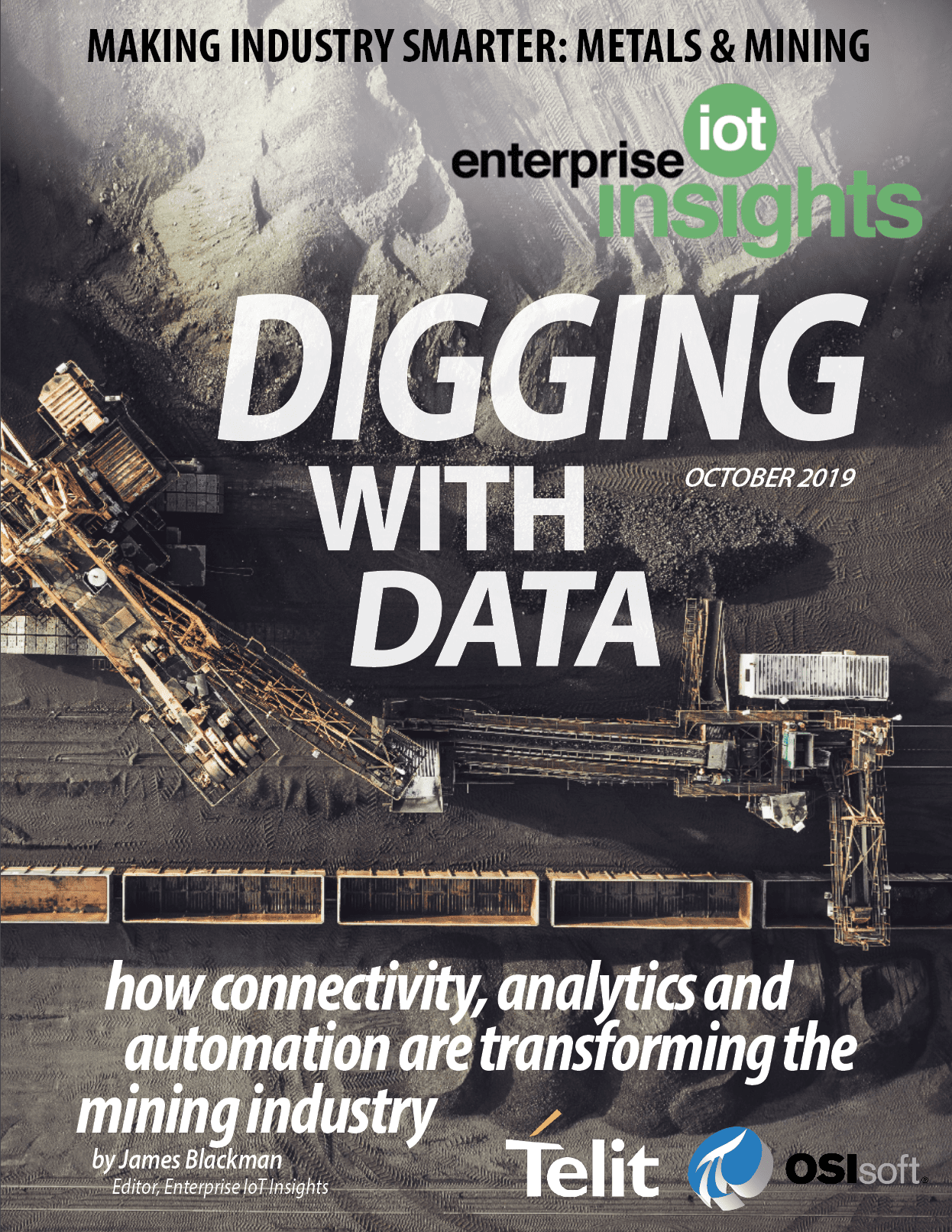

Picture the scene. A kilometre below the surface of the earth, perhaps three, a steel canopy, a couple of metres high, perhaps less, protects workers from the ceiling falling in around them. Adjacent, a shearer goes back and forth across a wall of rock, like a slicer through a block of cheese. The rock falls onto conveyors, running for many kilometres to hoists, to be lifted for processing above ground.

In time-lapse, over months and years, the ore-carrying seam is cleared out, with the canopy and shearer moving in sequence along face after face, before being collapsed and reassembled nearby, in another hole in the ground.

For big mining companies, this operation is multiplied out, across several sites. Over a generation, a labyrinthine network of underground rock-walls is hoovered up, and the mine is shut down. The mining company moves to the next venue, trailing its equipment and workers like an irregular circus, in black and white.

For big mining companies, this operation is multiplied out, across several sites. Over a generation, a labyrinthine network of underground rock-walls is hoovered up, and the mine is shut down. The mining company moves to the next venue, trailing its equipment and workers like an irregular circus, in black and white.

This is longwall coal mining, a hard discipline from the industrial age, which is struggling to stay relevant in the digital era, as technology (and higher environmental stakes) makes large-scale production of renewable energy viable, and as digital communications struggle to navigate the sector’s bleak terrains.

Mining is an industry, afflicted on all sides, which has struggled to modernise, especially deep underground. For ages, the sector has apparently shrugged at the promise of digital change, too.

“Some executives were asking just a few years ago what they need technology for; that they’re just crushing rocks and extracting minerals. Which is right – that is what mining is. But those companies are shutting down now. They are spending way too much on energy and [other] costs. They need technology to cope with the pressures on the industry,” says Martin Provencher, industry principal for mining at California data integration company OSIsoft.

Quite apart from the (long, inexorable) shift towards renewables, the problem for mining is the market has destabilised during the past two decades with the rising influence of financial markets, bringing extreme price inelasticity to the trade. This volatility is exploded in certain related disciplines, such as in aluminium and steel production, where China has skewed supply-and-demand.

“It used to be relatively easy; you could see the cycles coming, every 10 to 15 years, for the last 200 years. You could prepare – you could shut down, reduce production, schedule maintenance. But the market is very unstable now. You don’t know what the commodity prices will be doing tomorrow,” says Provencher.

ROUGH TERRAINS

In truth, the sector’s struggles with digital technology are circumstantial, undermined by the roughness of its working conditions, more than the stubbornness of its protagonists. Provencher admits as much; the biggest mining companies are grasping the nettle of digital change, he says.

“There are mining companies that are already operating machinery remotely, 1,500 kilometres away, somewhere in the middle of Australia. So you can’t say this sector’s lagging behind.”

There is a digital divide in mining, like in every walk of industry, says Ian Hughes, senior analyst in IoT, 451 Research. “Mining has a split, where a few very large companies have very advanced capabilities, but a large number remain untouched by digital transformation, until the tools they use start to become more digitally enabled.”

He suggests, despite the periodic roving for new sites, that mines are fundamentally intransient. “They work to find the resource they were built to extract – so there are fewer opportunities to change processes than in something like manufacturing, which may alter the raw materials or the design of the end product.”

But Jared Evans, co-founder and chief operating officer at MAJiK Systems, an Ontario-based industrial analytics provider, suggests the urgency to upgrade technology is keener in mining, in fact, because it requires such effort and capital to get started.

“It is either in start-up mode or roll-up mode, for most of the life of the mine. There’s the commission period, where the mine is being built, before any mining happens and before anyone makes any money; and then there’s the cleanup and shut down afterwards,” he says.

This has focused minds, he suggests. “The mining industry embraced the idea of technology faster than traditional manufacturing in order to be profitable as soon as possible.”

Milena Milosevic, head of business development for EMEA at IoT module maker Telit, adds: “Mining has a physically dynamic production space, which changes every day. The more technology can make asset reconfiguration easier, the better.”

Swedish telecoms vendor Ericsson, says the same, explaining away the slow-burn of digital in the mining space. “It takes years, sometimes decades, to set up a mining site,” comments Erik Josefsson, vice president and head of advanced industries for the Swedish outfit.

Swedish telecoms vendor Ericsson, says the same, explaining away the slow-burn of digital in the mining space. “It takes years, sometimes decades, to set up a mining site,” comments Erik Josefsson, vice president and head of advanced industries for the Swedish outfit.

“Business is planned long-term. Industrial solutions are checked thoroughly. Most equipment gets ruggedized to handle harsh environments. So mining companies check new technology intensively before deciding to invest.”

The problem, then, is mines are rough venues for sensors and data. Deep underground, or in desert and tundra, or across vast quarries and rock mountains, even the best laid plans go awry, it seems. Here, everyone agrees.

“It has just proved very difficult for these companies to get connectivity through these mines, because of their harsh environments and the way their equipment is used,” says Evans.

Josefsson comments: “Mining is ‘unconnected’ by default. It moves, with blasting and new tunnelling. The need for wireless is clear but existing solutions have struggled to meet stability and safety requirements.”

BIG OPPORTUNITIES

But we will come back to the gnarly challenge of connectivity; let us first consider the opportunities from connecting machines and integrating data in the mining industry, which everyone agrees on, whatever their view of the communications architecture to realise them.

The opportunities for digital technologies in mining, if only they can be harnessed, are considerable, offering a way to bring intelligence to operations that spread as far over ground as they do below it.

“You have to remember: a mine isn’t just a hole in the ground; there’s everything to do with how you’re processing the ore, and whatever processes before it gets shipped [for refinery]. You’re building a factory on top of this other construction site, drilling down to the mineral you’re trying to extract,” says Evans.

“There’s just so much that goes into building a mine, and there’s so much that’s in the critical chain to deliver value from it. Any one of those machines or systems, if they break down, costs money and delays profit.”

This is the main reason to invest in technology, for any organisation in any sector: for managing business. All of the opportunities discussed in this section – covering productivity, efficiency, maintenance, safety – are encompassed in this.

In mining, as discussed, business is volatile, subject to the high ebb of operational spend, on energy and resources, and the crashing cycles of capital investment. Costs need to be brought in line. “The only way is to be sure your costs are [controlled] enough that you’re making profit, or at least making enough that you’re covering them,” remarks Provencher.

And the way to achieve this is to drive productivity on one side, and efficiency, including around costs, on the other. New digital technologies, making constant measures from (and adjustments of) machines and processes, are useful to bring accuracy to operations and minimise waste in inherently messy processes.

“Some companies are behind, some are way out in front; but there is huge potential for all of them. Even for simple mines, even for quarries in the cement industry, say, you blast with explosives and crush the rock, to get the mineral – but even just doing this, there is lots of opportunity,” he says.

Josefsson adds: “Optimising production cycles is a primary target. Even small-cost reductions amortize over millions and billions of cycles.”

Smarter analysis of operational data, gleaned from machines and processes, brings control and insight, and a platform to drive improvements in performance. “If you can produce more good material with the same tonnage, then that’s good,” notes Provencher.

This article continues here (part 2). It is also available to download (for free) in full, as a standalone report – from here. The report features additional information. It forms part of Enterprise IoT Insights’ ongoing Making Industry Smarter report series, which has also covered Energy & Power, Agriculture & Farming, Supply Chain & Logistics, Cities & Towns, and Production & Manufacturing.